The rating agencies have recently confirmed that Romania managed to avoid a downgrading of the sovereign rating to “junk” thanks to the newly adopted fiscal and budgetary measures. Such a rating would have had a severe negative impact on the country’s development prospects, while Romania needs, besides healthier public finances, sustainable economic growth. A major risk has been avoided, yet the next period is crucial, as adjustment efforts must be strengthened through effective implementation and extended through reforms, in a consistent and predictable framework.

The reconfirmation of the investment grade rating for Romania signals confidence but does not remove the risks associated with the fiscal and external imbalances.

Urgency of consolidation of public finances

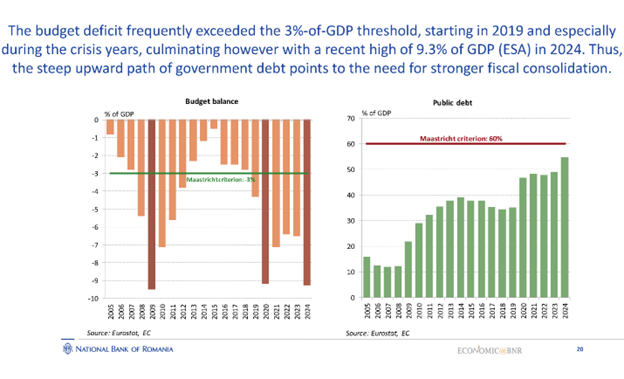

The imperative need for the general government budget correction has emerged amid objectives that have already been or have now become a priority – exit from the excessive deficit procedure, public debt sustainability, reduction of external imbalances. The urgency of budget adjustment has arisen after the fiscal slippage in 2024, when Romania reported an ESA deficit of 9.3% of GDP, the largest general government deficit in the EU.

The deficit adjustment has begun even with this year’s budget, mainly via measures to freeze public sector wages and pensions. Yet the budget planning for 2025 has also proven to be fragile, severely underestimating the budget deficit. After only a few months of budget execution, the estimated deficit jumped from 7% of GDP (according to the Budget Act) to approximately 9% of GDP or even higher (according to mid-year estimates). These developments called for stronger efforts aimed at budget correction, which were reflected in the content and size of the “First package”.

Under the circumstances, the debate has been captured by various opinions on the scale and effects of the so-called “packages of measures”. It is essential to filter and prioritize measures via a multiannual fiscal strategy, which would provide efficient solutions and minimum predictability for the entire adjustment period, and beyond.

Worth mentioning is that the National Medium-Term Fiscal-Structural Plan agreed with EU institutions at the end of last year envisaged a gradual correction of the budget deficit, at an average annual pace of around 0.8 percentage points of GDP. Nonetheless, these projections were based on a more optimistic starting point, under the assumption of meeting the target deficit, when the economic outlook was much more favorable to the assumed pace of adjustment. At that time, we looked at the scenario of a gradual adjustment (therapy).

Currently, following the substantial deviation from the deficit target for 2024, but also from that for 2025, the package of measures is estimated to have a cumulative budget impact of almost 4 percentage points of GDP for 2025 and 2026. Hence, the adjustment effort would enable nearing the initially projected budget deficit target.

In this context, due to the scale of the measures and amid a public narrative rife with austerity messages, although rather not substantiated, the image of a sizeable budget correction has taken shape, with fatalistic references to Greece in 2009, when the Greek state defaulted.

However, … Romania is not Greece!

Has Romania been on the edge of the precipice in which Greece plummeted in 2009?! Romania now is fundamentally different from Greece back then, having an economic framework that is much more resilient to a deep global financial crisis, such as the 2008-2009 crisis. Greece had to solve its defaulting via the forced signing of several vital bailout agreements with the EC, the ECB, and the IMF (“Troika”) and debt forgiveness deals, unprecedented in the recent history of sovereign debt restructuring episodes.

When looking at the picture of an economy badly in need of budget correction, the most relevant aspects that must be assessed responsibly refer to both the size of imbalances and the overall performance of economic activity.

Romania’s fiscal slippage in 2024 (-9.3% of GDP) was indeed in tandem with a current account deficit (-8.4% of GDP). These values are, however, less troubling than those Greece recorded in 2009 (budget deficit of 15.4% of GDP and current account deficit of 12.5% of GDP).

Another set of benchmarks refer to government debt, which in the case of Greece neared 130% of nominal GDP, the external debt standing at 180% of GDP. Moreover, the exposure of the European banking system to Greece’s public debt was impressive, especially for banks in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, with severe contagion risks.

At end-2024, Romania’s government debt stood at 55% of GDP, trending upwards, while its external debt was 58% of GDP, which is nothing like Greece’s situation.

The resilience of the Romanian banking sector remains adequate in terms of its financial soundness indicators, yet some aspects must be considered more cautiously, namely the increase in the banking sector’s balance sheet driven by the government’s financing needs. The interlinkage of the banking sector and the government sector has become stronger over the last years, banks’ loans to government and holdings of government securities (approximately 25%, average for the past three years) being the largest in the EU. In this vein, joint efforts must be made to pull Romania out of the area of low financial intermediation, which hinders the structural transition toward high value-added sectors.

Last but not least, mention should be made of Greece’s shaken credibility, dented back then also by the manipulation of statistical data, especially those on the budget deficit. By contrast, Romania currently fully complies with the standards for statistical reporting and fiscal transparency, which are essential for credibility in the relationship with European institutions. Romania is concerned with maintaining the confidence of EU Member States through actions that should also ensure certain negotiation margins for accessing EU funds, which is crucial for preserving the economy’s growth potential.

On the other hand, concerning the necessary budget adjustment, the preliminary debates sought to accredit the scenario of a consolidation achieved solely by cutting public spending, as in the case of Argentina, in order to avoid the recessionary effects of fiscal measures. However, it must be understood that the fragility of public finance is structural, given that Romania has recorded, for many years, the lowest tax revenues in the EU (approximately 27% of GDP), except for Ireland.

Moreover, an adjustment made only on the expenditure side would have required spending cuts beyond the limits of functionality of the government and public services, whereas Romania has undertaken investment objectives and security commitments that cannot be neglected.

However, … Romania is not Argentina!

President Javier Milei’s “zero deficit” program has been bandied about a lot as a good example of efficiency in reducing public spending, yet this overlooks the fundamental differences between the constitutional and legislative systems, national priorities and, most importantly, the economic backgrounds in question.

One should not fail to remember that the reforms in Argentina came as a response to an unprecedented economic crisis, when the annual inflation rate had neared 300%, and the deficit was reduced on the back of massive cuts in government expenditure – by shutting down government offices and state entities, making large-scale layoffs, stopping the funding of many national programs.

The Milei administration slashed Argentina’s healthcare budget almost by half. Thousands of healthcare jobs were axed. Closing public authorities, halting early cancer screening programs, freezing federal funds for vaccination campaigns, reducing the medical care services package for retirees are all measures that brought budgetary savings, but at what social cost?!

In the same vein, the education budget was cut nearly by half, and 68 Nobel Prize laureates in Chemistry, Medicine, Economic Sciences, and Physics wrote a letter to Argentina’s president, expressing their concerns about the drastic cuts in science and technology funding, and their impact on the country’s development.

Romania’s administrative system surely needs in-depth reform, but one that derives from the redesign of administrative flows and is focused on increasing the administrative capacity and efficiency in the relationship between the state and its citizens. At the same time, data show that the fiscal space is relatively contained in terms of the state apparatus.

Out of the 1.3 million budgetary sector positions, 64% of employees are in central government and the rest in local government. Of the approximately 836 thousand positions in the central government, 24.6% are in the defense, public order and national security sub-sector. At the current juncture, potential cuts in this sub-sector would run counter to any objective of strengthening the security and defense policy.

Education and healthcare sub-sectors taken together, at central and local levels, comprise little over 630 thousand positions, i.e. almost half of the budgetary sector positions. Approximately 150 thousand positions are in educational and healthcare facilities financed entirely from own revenues, in a context where the two sub-sectors face severe labor shortages in terms of both numbers and especially skills.

Last but not least, Romania has an administrative organization, a legal system and political institutions much different from Argentina’s. For Romania, the role of the state and the priorities in terms of public spending must take into account another range of constraints and opportunities, related primarily to the country’s own development path, but also to its EU membership, with all its requirements and benefits.

Making parallels to certain international models by citing some disparate effects or similarities is not a proper approach for Romania. Rather, targeted actions are needed, thoroughly substantiated and correlated with national and European priorities.

And yet, a key lesson can be drawn from Argentina’s case: the need to avoid pro-cyclical economic policies by creating fiscal and monetary policy space during expansionary periods so that in downturns of the economic cycle the necessary adjustments can be implemented gradually, without the excessive social or economic costs that Argentina has incurred.

A predictable and balanced adjustment

Romania is not Greece, so there is no need to talk about the default scenario. Romania is not Argentina, so there was no hope of cutting the budget deficit solely on account of expenditures. Between these extreme examples of adjustment, the necessary path is a balanced adjustment that addresses both the exigencies of fiscal consolidation and the need for sustainable economic growth.

The large scale of the budgetary correction needed by Romania shows, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that the deficit adjustment could not be achieved only by curtailing expenditures, without fiscal measures that would also boost revenues, not only immediately, but on a permanent basis.

Given the structure and scale of the fiscal consolidation program, there is justified apprehension that the adjustment measures, mostly the rise in taxes, will take their toll on the economy and its growth, and hence also on the efficiency of fiscal consolidation. Therefore, the concern about fiscal correction ought to be backed by the interest in mitigating the restrictive effects of the adjustment measures on the economy or counterbalancing them via policies to support economic competitiveness.

Nonetheless, these policies must not amount to a watering down of the fiscal deficit reduction goal or to a delay in structural reforms aimed at restoring the confidence of both entrepreneurs and households in government authorities.

The real success in the face of the current challenges is the implementation of public policies that strike a balance between adjusting deficits and supporting economic growth. Without tackling the budget deficit, structural problems deepen, confidence declines, risks increase, and opportunities are missed. In the absence of sufficiently robust economic growth, fiscal consolidation efforts could lack the expected effectiveness.

Over the short term, despite fiscal consolidation, amid economic stagnation and budget rigidity, public debt might keep rising above 60% even in the coming quarters, and significantly above this threshold in the longer run.

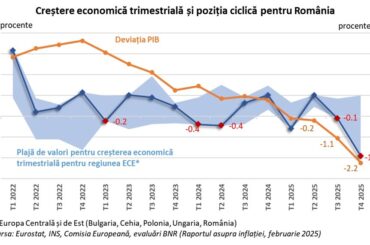

Recent forecasts have shown that Romania appears to get bogged down in a realm of fragile economic growth of less than 1% annually or even 0.5% for this year according to the latest estimates. Hence, the major risk is to go through an episode of stagflation. However, such an evolution does not chime in with the current regional and global economic environment, for which the economic projections have not worsened as much as in the case of Romania.

Having contracted by 3.3% in 2024, investment rose by 5.5% in 2025 Q1, yet this performance cannot be viewed as a sustainable recovery, given the stagnation of industrial production compared to the end of last year, which reflects trade policy-related uncertainties, but also the cyclical weakness of European partners’ economic activity. Moreover, capital accumulations are conditioned both by the absorption of EU funds, with significant risks derived from the failure to fulfil the targets and milestones Romania committed to, and by direct investment flows, marked by the successive drops over the past two years of about EUR 3 billion and EUR 0.7 billion respectively.

Turning to the NBR’s monetary policy stance, during hard times the central bank must capitalize as much as possible on the existing credibility flow, especially amid a temporary bout of inflation triggered by the transitory shocks associated with the recently adopted fiscal measures.

The monetary policy currently has a challenging task as it acts in an environment fraught with the persistent effects of inadequate economic policies. This essentially refers to the fiscal policy slippage in the 2024 election year, which prompted the ballooning budget deficit and the severe weakening of public finances. The easing of monetary conditions in mid-2024 could also be viewed through a procyclical lens, as that was when the strongly expansionary fiscal environment could be better correlated with inflation expectations, but also with the impact of the impending fiscal corrections starting as early as 2025.

What we are currently facing is a sudden, strong resurgence of inflation. Nonetheless, given the transitory nature and fiscal root of price hikes, the concern is to have balanced monetary conditions in place by moving toward a countercyclical pattern, especially in the event of a near-stagnation scenario.

This is why it becomes crucial that the fiscal consolidation measures should, to some extent, be offset by growth-enhancing policies. It is of the essence to protect key investments, especially in infrastructure, which have stimulative effects on economic growth. The policies to support private sector competitiveness via using EU funds, boosting foreign investment and strengthening domestic capital must be a top priority as well.

In this vein, it is vital to stick responsibly to the path of reform, but also to prepare for accession to the OECD, which fosters positive investor perceptions and new development opportunities. Therefore, political stability and social peace are now, more than ever, key ingredients to successfully overcoming current challenges.

P.S.: The charts below are part of the study entitled European Romania – developments, progress, challenges, conducted within the Economic@BNR analysis project of the National Bank of Romania.

1 August 2025