Guvernatorul Bancii Nationale a Ungariei, Gyorgy Matolcsy, a semnat recent un articol care a ridicat, probabil, multe sprancene printre oficiali din UE (“It is time to recognize that the euro was a mistake/Este momentul sa admitem ca euro a fost o greseala”, Financial Times, 4 November). Deoarece este o diatriba la adresa monedei comune, care, se afirma, ar fi fost o stratagema a Frantei de a tine ancorata Germania in Uniune. Intr-un fel, suna precum faimoasa expresie a Lordului Ismay: ca NATO este o alianta necesara pentru a-i tine pe rusi afara, pe germani sub control si pe americani in Europa. Textul contine o serie de observatii la adresa euro care, sub diverse forme, au fost in dezbaterea publica de-a lungul anilor. Astfel, nu putini economisti au deplans ca moneda comuna a fost introdusa fara a avea aranjamente fiscale adecvate. Insusi Otmar Issing, primul economist sef al Bancii Centrale Europene, a remarcat acest fapt. Sa amintim ca Raportul McDougall din 1977 constata ca o uniune economica si monetara va fi fragila daca nu va beneficia de un buget comun semnificativ. Este evidenta si o divergenta economica intre Nordul si Sudul zonei euro, care nu poate fi explicata numai prin factori ce nu tin de functionarea uniunii monetare.

Este greu sa respingi ceea ce este de bun simt economic, parti constitutive ale unei gandiri consolidate privind ce ar defini o zona euro robusta: aranjamente de “partajare a riscurilor”(risk-sharing), inclusiv o “capacitate fiscala”, care sa nu fie cu statut inferior aranjamentelor de reducere a riscurilor (risk reduction), un fond de rezolutie solid, o schema colectiva de garantare a depozitelor (EDIS), reguli fiscale care sa nu ampifice pro-ciclicitatea cand este nevoie de corectii macroeconomice de amploare, o pozitie (stance) macroeconomic la nivelul zonei euro si, nu in cele din urma, un activ sigur (safe asset) care sa ajute euro sa fie o moneda de rezerva competitiva in spatiul global. O chestiune la care face aluzie Guvernatorul Matolcsy, este ca ratiuni de ordin politic au impiedicat, sau incetinit, reformarea design-ului institutional al zonei euro. As mentiona ca este ironic ca Germania, care se poate spune ca este marele castigator economic al introducerii euro pare sa subaprecieze aceasta situatie; fiindca moneda comuna a operat precum o marca germana subevaluata, ceea ce explica, in larga masura, mari surplusuri ale balantei sale externe. In aceeasi categorie putem include si Olanda.

Dar una este sa observi neajunsuri in formatul institutional si mecanisme ale zonei euro si altceva sa consideri ca euro a fost o eroare strategica. Daca acceptam ca moneda comuna are menirea de a sustine Uniunea Europeana in competitia globala si sa ajute mentinerea stabilitatii in Europa, aparitia sa era inevitabila la un moment dat. Ca introducerea euro a fost poate prematura este o teza cu mica relevanta acum. Ce conteaza in schimb sunt hibe de constructie, care nu aveau cum sa nu aiba consecinte; unele dintre hibe au fost subestimate de politicieni, altele au fost insuficient intelese inclusiv de nu putini economisti.

Dar sa judecam istoria si destinul monedei comune cu beneficiul analizei retrospective si in perspectiva temporala. In 1999, China nu era inca gigantul economic (si nu numai), aparent tot mai amenintator. Iar SUA nu se conturau drept un rival economic atat de taios pentru Uniune, intr-o lume ce se multipolarizeaza, in care NATO si relatia transtalantica din nefericire slabesc. Exista totodata lanturi de productie ce exprima integrare economica de profunzime si care pot reduce din eficacitatea utilizarii politicilor monetare independente ca instrumente de corectie macroeconomica –desi m-as feri sa afirm ca politica monetara nu mai are utilitate in economii nu pitice (ex: Cehia, Polonia, Romania, Ungaria) in comparatie cu tari care au folosit/folosesc regimuri de consiliu monetar. Sunt de subliniat si pericole mari noi, care reclama un raspuns colectiv, intr-o Uniune ce are nevoie de coeziune interna.

Opinia ca o recompunere a zonei euro ar face UE mai robusta nu mi se pare convingatoare. Daca zona euro s-ar fragmenta, aceasta ar lovi proiectul european, probabil in mod fatal. O asemenea evolutie ar fi rea pentru toti, pentru relatia transatlantica. Si NATO ar avea mult de suferit.

Zona euro are nevoie de reforme profunde in functionarea sa pentru a deveni robusta, pentru a face moneda comuna robusta si pentru a sprijini Uniunea in ansamblu. Propunerea minstrului german de finante, Olof Scholz, privind schema colectiva de garantare a depzitelor este un pas inainte, chiar daca modest. Si este de sperat ca propuneri din documentele de reflectie ale Comisiei Europene din 2017, din alte documente serioase, vor gasi intruchipare in realitate; cu cat mai curand, cu atat mai bine. Nu trebuie sa asteptam o noua criza severa pentru a ne trezi la realitate, pentru a face “orice este necesar pentru a salva euro”( whatever it takes to save the euro) –ca sa repet declaratia ca si magica a lui Mario Draghi din iulie 2012.

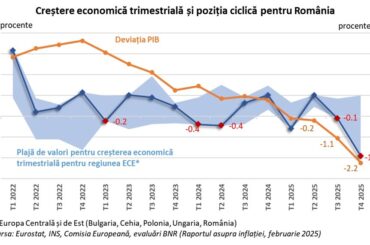

Reformele in mecanismele zonei euro, pentru a o face robusta, sunt salutare pentru tarile care nu sunt inca in Uniunea Monetara. Economia romaneasca are de atins o masa critica de convergenta reala si de realizat consolidare macroeconomica durabila (controlul durabil al deficitelor) pentru a intra in Macanismul Cursurilor de Schimb (ERM2) si apoi, in zona euro.

The single currency needs a robust euro area

The Governor of the National Bank of Hungary, Gyorgy Matolcsy, wrote a piece recently that has, quite likely, raised many eyebrows in the EU (“It is time to recognize that the euro was a mistake” , Financial Times, 4 November). For it is a sort of a diatribe against the euro, which, allegedly, was a French ploy to keep Germany well anchored in the EU. In a way, it sounds like Lord Ismay’s famous saying that NATO is needed to keep Russians out, Germans down, and Americans in. The text contains a range of grievances, some of which have been in public debate, under various shapes, over the years. As a matter of fact, many economists decried the introduction of the common currency without proper fiscal underpinnings. Otmar Issing himself, the ECB’s first chief economist, talked about it too. And let us remember that the McDougall Report of 1977 concluded that an economic and monetary union needs a significant common budget to make it viable. An economic divergence between the North and the South of the euro area is also evident and it cannot be ascribed to extra-euro area phenomena only.

One can hardly refute what is commonsensical and, more or less, part and parcel of a collective wisdom regarding what the euro area needs to become a robust construction: risk-sharing instruments (including a “fiscal capacity”’) which should not be “junior” to risk-reduction measures, a solid Resolution Fund, a collective deposit insurance scheme (EDIS), “smart” fiscal rules (which should not amplify pro-cyclicality in times of badly needed correction of imbalances), a collective macroeconomic policy stance and, not least, a joint safe asset that should also help the euro be a more competitive global currency. A problem, that is alluded to by Governor Matolcsy, is that political hindrances have stalemated advance. And I would add that, ironically, Germany, which is, arguably, the biggest economic winner of the creation of the single currency, seems to underplay this reality; for the euro has operated as an undervalued Deutsche Mark, which explains its formidable current account surpluses, year after year, to a large extent. The Netherlands is in the same category.

But it is one thing to notice major flaws in the euro area design and functioning, and another thing to state that the euro introduction was a strategic error. If one accepts that the euro is a strategic and political construct to help the European Union in global competition and maintain peace in Europe, its creation was inevitable. Whether its creation was premature is irrelevant now. What are relevant instead are the weaknesses of its design, which could not have been inconsequential; some of these weaknesses were dismissed by politicians, and others were poorly understood by not a few economists at the time as well.

But let us judge the history and the fate of single currency with the benefit of hindsight and in a forward perspective. In 1999, China was not the seemingly unstoppable economic (and not only) juggernaut it is today. And the US were not, at the time, a bitter economic rival of the EU, which they seem to become in a world of proliferating “first would be nations” and when NATO and the transatlantic relationship are, unfortunately, weakened. There are also European value chains in the euro area, in the EU, which reflect pretty deep economic integration and which may dent the potency of independent monetary policies as adjustment tools –though I would refrain from saying that independent monetary policies are devoid of any usefulness for larger New Member States (such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania) as against currency board regimes. There are also all kind of new major threats that demand a collective EU response, a cohesive union.

A belief that a partial, or complete, dissolution of the euro area would make the EU stronger is not convincing at all. A dynamic of events along such lines would probably cripple the European project fatally. And such a denoument would be bad for everybody, for the transatlantic relationship as well. NATO would be much damaged as well.

The euro area needs profound reforms to become robust and, thereby, strengthen the single currency and the EU as a whole. German minister Olof Scholz’s proposal about EDIS, though not ambitious enough, goes in the right direction. And, hopefully, key proposals one finds in the EC reflection reports of 2017 and in other analytical documents will turn into reality; the sooner the better. One should not wait for another deep recession to turn bold and do “whatever it takes to save the euro”, to repeat Mario Draghi’s famous statement of July 2012.

Reforms in and of the euro area, to make it robust, would be more than welcome in accession candidate countries. As for its part, the Romanian economy needs to achieve a critical mass of real convergence and control its imbalances on a sustainable basis in order to enter The Exchange Rate Mechanism2 and, after that, join the euro area under auspicious terms.