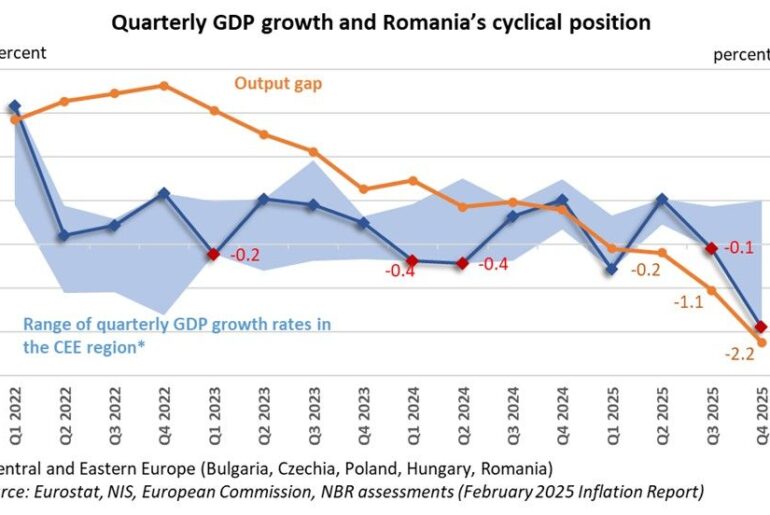

Over the past few days, we have witnessed intense debates around the topic of the “technical recession”, where various causes…

History has shown that inflation is the most perfidious economic threat to the well-being of nations, with far-reaching redistributive effects…

The expansion of the crypto assets sector, including “stable coins”, is welcomed by those involved in this activity and by…

To answer on whether and how global capital flows should support the building of young democracies I would use two perspectives.…

The Draghi report is exceptional through its thoroughness and daringness to tackle critical issues for the EU,s future. Some of…

AI can augment speculative behaviour and foster panic, more instability, especially when financial markets are not adequately regulated. AI can…

The big crisis that erupted in 2008 showed glaringly that very large borrowing and poor regulations can put economies into…

In another text, I argued that AI does not alter economic logic/rationality, nor does it eliminate competition, income and wealth disparities among individuals and groups of people, or between societies/states (“Can AI change economic logic?” Hotnews and Contributors, January 28, current year). What public policies aim to do is to mitigate such disparities and derived social tensions within economies. Internationally, interventions are carried out by specialized international financial bodies such as the IMF, while in the EU, various stabilization mechanisms and structural and cohesion funds operate.

A related question is whether AI can prevent financial or economic crises. The almost automatic answer is no. Because AI does not change economic logic or rationality, and competition does not disappear. In other words, business/economic cycles do not vanish, whether we consider short and medium-term fluctuations in economic activity or longer-term ones generated by investment cycles and major technological breakthroughs that induce technological cycles.

Debates on artificial intelligence (AI) have intensified greatly in recent years. The British government organized a high-level conference on this topic recently. Top officials from the EU and the USA consider AI among their priority policy orientations. Prominent Silicon Valley voices, major companies, are actively engaged in this debate. In Asia, AI is at the forefront of attention. At last year’s annual meeting of the Academia Europaea, Professor Helga Nowotny’s inaugural address and other lectures focused on AI. While the benefits of AI are widely acknowledged, deep concerns about its potentially harmful effects and the possibility of it spiraling out of control are also raised. Can AI be regulated without stifling innovation? Could AI address imbalances between needs and resources sustainably by bringing about abundance for all? This debate is particularly relevant given the significant disruptions of recent years, that have perturbed people’s lives and have led to a “cost of living” crisis with political ramifications.

After almost two years of battling price pressures by embarking on one of the most aggressive hiking cycle in economic history, central banks seem fully committed to go even further with their tightening campaign to rein in runaway inflation should the case be.

This is a battle that central banks can’t afford to lose. Price stability is the ethos of monetary policy and central banks shall remain resolute in their purpose to return inflation to target and preserve their hard earned credibility. But the devil is in the details and even though the destination is well know, there are many unchartered paths and possible journeys, whose choice will reverberates in the years to come.

![Finance and democracy: a more complicated relationship than meets the eye[1]](https://opiniibnr.ro/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/democracy-7579742_1280-770x461.jpg)